As we discovered in this article, the Bird-Jones is a type of catadioptric, or compound, telescope which is usually targeted at beginners. They’re often sold under trusted brand names by big box stores, and in my experience most people who own them only use them once.

Previously we looked at what a Bird-Jones telescope is, how it works, and why people hate them. And while all this information is interesting, it doesn’t tell us much about the experience of actually using one.

In fact, I’d wager that more than half the people on Internet forums warning others about Bird-Jones scopes have never actually used one—including me.

To remedy this situation, I borrowed a friend’s Celestron Astromaster 114AZ.

In addition to the 114mm optical tube, the kit includes:

- an alt-azimuth mount

- a steel tripod

- two eyepieces: 20mm

- some planetarium software

Setting it up, I thought, “This doesn’t look too bad.” The stubby optical tube seems decent enough, and the 1.25” rack-and-pinion focuser isn’t the worst I’ve seen. The alt-az mount should, in theory, be more approachable for the newcomer than the EQ1-style equatorial mount that is usually supplied with this sort of scope.

I had some concerns about the eyepieces. Namely, the 20mm is labeled as an erecting eyepiece, but the erecting prism assembly came in a separate baggie along with a threaded plastic retaining ring. I tried putting it together but nothing doing. No matter; I decided I would give the scope a fair shot with my 17.3mm Delos eyepiece instead, providing slightly higher magnification than the 20mm, but with a significantly larger true field of view.

My first issue was with the mount. Aside from being flimsy, it also relies on you unlocking the altitude clutch whenever you want to move the scope and locking it again once on target.

This makes for highly imprecise aiming, as the scope will jiggle and shift when the clutch is loosened or tightened.

It also tends to sag after being locked down; I found I had to aim above my target and let the scope drop into the desired position. This might have been mitigated by adjusting the balance, if only I could slide the optical tube forward in the tube rings. But Celestron built a plastic brand plate onto the side of the scope which prevents this possibility.

But we’re here to find out about the optics, not the mount.

My first impression was a dismal one. The corrector lens didn’t seem to do much in fixing any aberrations, as the primary mirror exhibited worse coma than I’ve ever seen in any telescope. As soon as stars moved out of the center of the field, they became super-elongated, growing into bright flares. Only in the central portion of the field were the stars even remotely point-like. I could tell right away that collimation was off by quite a bit, but I managed a reasonably decent view of the Orion Nebula, which looked about as bright and detailed as one would expect from a 4.5” mirror.

I might have spent longer looking around but the temperature was close to -15C and I had to pack up for the night.

My conclusion after one session: the optics were bad but clearly out of collimation, so it’s possible I didn’t give it a fair shake.

The mount was also an aggravating factor, especially with 1000mm of focal length. To really judge this telescope, I needed to get it collimated and more securely mounted before taking it for another spin.

Bird-Jones reflectors are known to be a pain to collimate. One of the reasons is that the corrector lens prevents the use of laser collimators. Another reason is the lack of a center marking on the primary mirror.

I’ve been using reflectors for about fifteen years now, and I’ve always relied on a simple collimation cap.

My current reflector is an f/4.9 collapsible Dobsonian, an instrument known for needing frequent, accurate collimation, yet I seldom spend more than five minutes adjusting the mirror and very rarely do I find the result less than acceptable. Maybe I’m less picky than some enthusiasts.

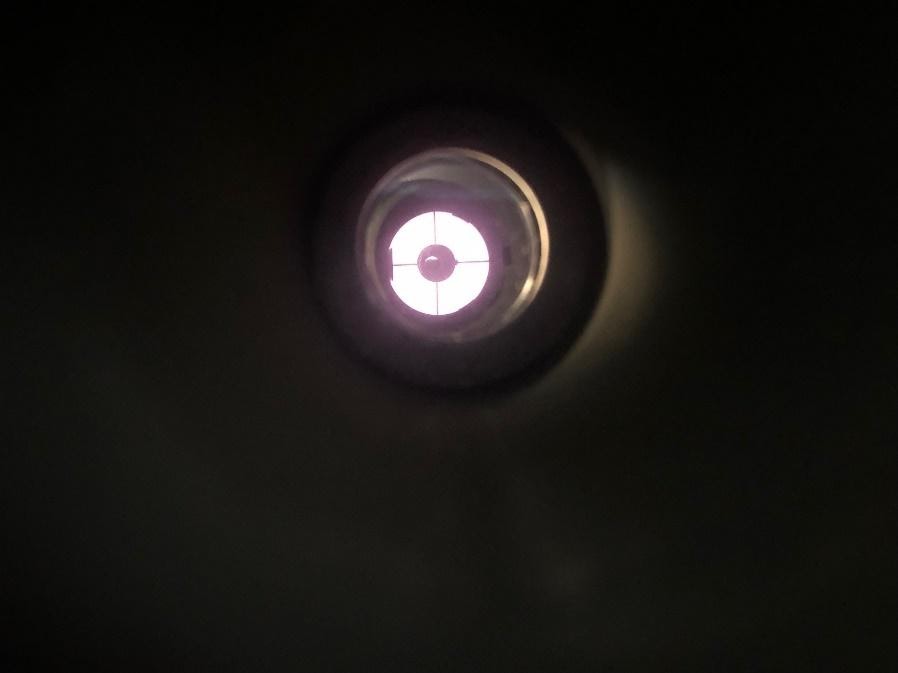

I had thought that the AstroMaster 114, being an f/9 instrument, shouldn’t give me much trouble, as I am used to collimating a f/4.9. But without a center marking on the primary, and without a collimation eyepiece at my disposal, I was left to eyeball the alignment of the mirrors using the Celestron manual for reference.

The corrector lens makes the mirrors seem much smaller or more distant; while I’m not sure how much this hindered my progress, I can’t say it helped at all either. The secondary is easy enough to adjust with an Allen key and works much the same as other Newtonians. The primary requires a screwdriver to loosen the mirror. There are three knurled thumbscrews for adjusting the tilt, but they are very stiff and difficult to turn and there’s little room to get a good grip on them.

Having done my best to get everything centered by eye, I brought it out into yet another extreme cold warning.

The Vixen-style dovetail plate fit nicely onto my Synta AZ4 manual mount, and this provided an infinitely superior platform for the telescope. Now I could easily aim it wherever I pleased and it would stay exactly where it was pointed.

Unfortunately, my collimation adjustments had little effect on the coma, both on-axis and off. Even in focus at the center of the field, stars showed asymmetrical spikes, and away from the center of the field, things got messy very fast.

Referring again to the manual, I attempted to fix the collimation using the star Rigel but none of my adjustments made any difference.

Overall, I found a lot of reasons not to recommend this telescope, even aside from the optics themselves. The mount is inadequate and frustrating to use. The supplied eyepieces are junk.

Collimating it properly involves significant work, such as installing a primary center marking and/or disassembling the focuser to temporarily remove the corrector lens. Of course, this is just one example of a Bird-Jones telescope; maybe I got a bad sample, and there are better ones to be had. But in terms of hardware and overall quality I think the 114AZ is representative of what you get when you buy one.

Many of these issues are not specific to Bird-Jones telescopes, but to cheap telescopes in general, and therefore experienced amateurs usually recommend Dobsonian-style telescopes which are much sturdier, better equipped, and simpler to use.

Using the 114AZ, I got the impression that if you happen to buy one with good collimation from the factory, put it on a better mount, and upgrade the eyepieces, you might have a usable telescope on your hands. But that’s a lot of “ifs”, and most people won’t be keen on spending hundreds of dollars on upgrades for a scope of this caliber.

In the end I think a 1000mm focal length is just too long to put on a shaky mount with no slow-motion controls.