You might already know the answer, but I’m here to offer a different perspective on how we think about the present moment and what is objectively real.

With all the hubbub about the James Webb Space Telescope and how it will be able to see the earliest epochs of star formation, many people I’ve spoken to are struggling with the concept of telescopes “seeing back in time”.

Is a telescope really a time machine? Is that truly how these things work?

The short answer: Of course not. If a telescope could see back in time, you could look through one and see yourself being born, or see your parents on their first date, not that you would want to see either of those things.

For people my age, we have Betamax tapes for that anyway.

I’m being cheeky here, but the point stands that there must be a difference between looking through a telescope and seeing back in time.

It might seem like I’m arguing semantics, but there’s more to the story than that.

To understand what people mean when they say a telescope can see into the past, we first need to get a clearer definition of the present.

Light Speed vs. Time

It’s common knowledge that light travels at a known, finite speed. Therefore, light which is emitted from some source takes time to reach an observer, and the image formed in the observer’s brain, or on their camera sensor, is of a certain age, defined by the amount of time the light had to travel.

We know that light travels 300 million kilometers in one year, so an image from a light source 300 million kilometers away will be one year old. (If you’re thinking that it sounds like we just described a light year, you are correct.)

Because space is so incredibly vast, most of the light we see from outside our solar system has been traveling for much longer than one year.

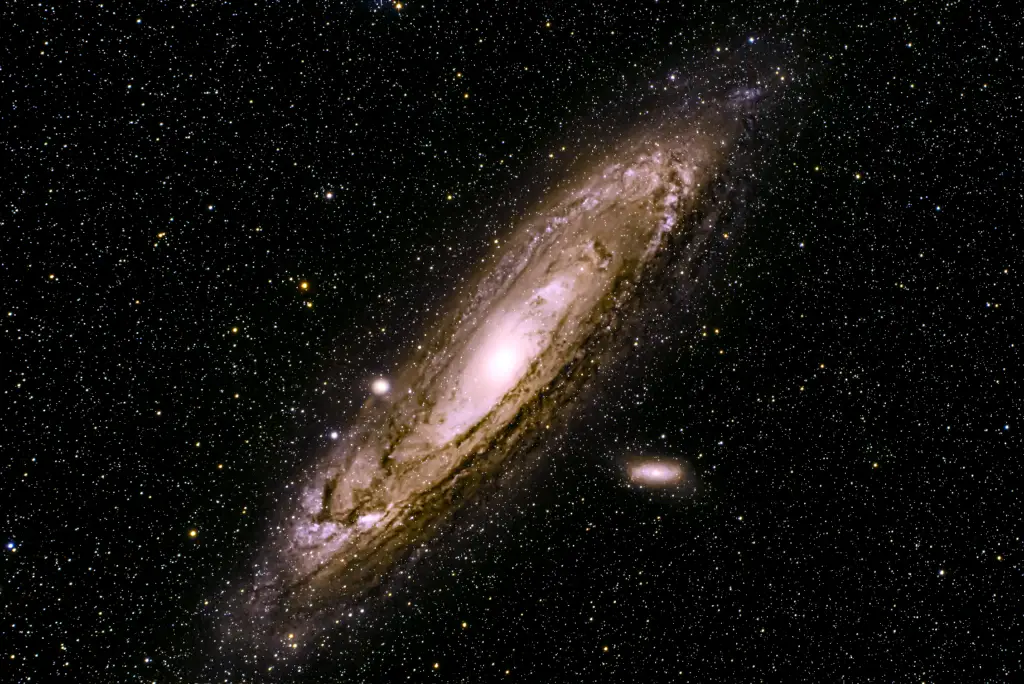

Consider that the nearest star is around 4 light years away, while the closest major galaxy is over 2 million light years away, or 19 million trillion kilometers.

The James Webb Telescope is expected to see over 13 billion light years into space, which should in theory allow it to glimpse the formation of the first stars and galaxies in our universe!

The thing that we say about these views of distant objects goes something like this: “We see them not as they are now, but as they were x number of years ago.” And while that sounds correct, this statement makes a huge assumption:

that there is an omniscient point of view from which someone could say what is happening “now” everywhere in the universe.

But Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity (1905) showed us that this is wrong; there is no single set of events which all observers would agree are happening right now.

This is called the relativity of simultaneity, and while it is too much to unpack in this article, the basic idea is that observers in inertial reference frames (meaning they aren’t speeding up, slowing down, or changing direction) who are in motion relative to one another will record a different order of events. And because in Special Relativity all frames of reference are valid and there’s no way to say which observer is “really moving”, we must accept that our ordering of events into past, present, and future is only relevant to our perspective and is not a universal fact.

But even if we forget about this concept, there is still another problem with the idea of “looking back in time”.

When you look through a telescope, you aren’t really looking into space. Rather, you are receiving signals from your environment. After all, your telescope doesn’t travel across the cosmos to find out what’s happening out there. It just sits and collects light from whatever it’s pointed at, just like your eyes.

And since all signals take some amount of time to reach you, everything you experience has, by definition, already happened.

What you call “the present” is in fact a collection of signals, either light speed or slower, which are reaching you at a given moment. This includes all distant signals from space. A telescope doesn’t transport you into the past; it just makes you more receptive to distant events happening in your present.

The key to making sense of all this is, once again, the speed of light.

It’s not just that light happens to travel at this speed; the speed is fundamental. It is the speed of cause and effect, a feature of reality which keeps everything from happening at once. The speed of light is the speed of information. This information defines our reality; our present moment is a collection of all past events for which information is currently reaching us, via visible light, radio waves, or any other forms of radiation.

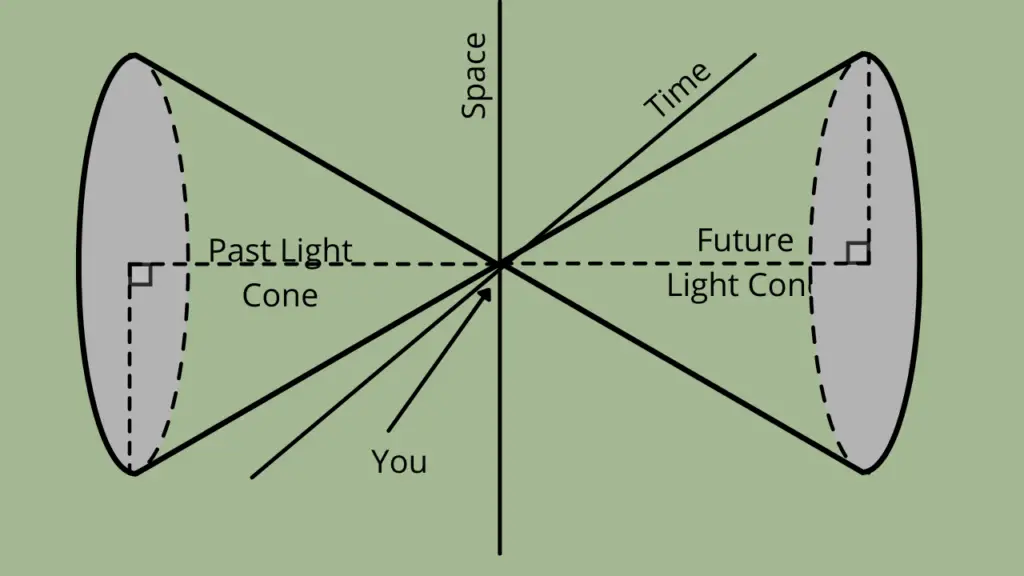

A spacetime diagram illustrates this perfectly.

This rather crude diagram illustrates the famous “spacetime continuum” that you might recall from science fiction, but it is actually derived from Special Relativity.

Three-dimensional space has been condensed into the vertical axis, while time is represented by the horizontal axis. The diagram is scaled so that light always propagates at 45-degree angles. This gives us constructs called light cones, with all light-speed signals embedded on the diagonal lines and anything slower than light, such as sound waves or other types of vibration, contained within the cones.

At a given moment in time, everything you are experiencing is contained on or within your past light cone, while any future events which might be influenced by you at that moment are contained in your future light cone. The diagram illustrates cause and effect and is something all observers will agree on regardless of their relative motion.

We can see immediately that events happening “now” which are separated from us by any amount of space are inaccessible to us, since the light takes time to reach us.

In other words, an event doesn’t become part of our reality until it is within our past light cone. There is no way we can describe events outside of our past light cone as objectively real since we have no way of obtaining information about them and can only speculate.

It is useless, therefore, to say, “That star might not exist anymore.”

If you can see it, or detect it using some equipment, it is part of your reality and it exists. There is no sense in talking about what might be happening outside of that past light cone. A telescope, even the James Webb, only allows us to see events further back in this light cone.

Let’s make up a scenario to illustrate this point. Suppose a star explodes in a supernova 10 light years away. 10 years later, someone turns on a light which is only 10 meters away. Both light signals reach you at the same moment. Both events are happening “now” from your perspective, even though both events occurred at different times in the past.

Intellectually, you may know that the supernova light is “older” than the light from the lamp bulb, but there is no way for you to obtain information about the older event first. This is not a limit of human perception, but rather a built-in limit to the speed of causality.

Additionally, we need to rethink our idea that light which has traveled great distances is old.

Another thing Einstein showed us in his Special Theory of Relativity is that light is timeless; it experiences neither distance nor duration. From the perspective of a light-speed particle, all places are “here” and all times are “now”.

Having said all that, let’s go back to the original question: Can telescopes really see back in time?

Though we have just determined that telescopes only show you more distant parts of your present moment, humans are clever creatures.

We have worked out the speed of light through measurement and calculation, and we have invented ingenious ways of estimating distances at cosmic scales.

Therefore, as we receive these light signals from increasingly distant sources, we can see our universe at different stages of its evolution. By gathering samples from millions of sources all over the sky, we have gained a vast amount of knowledge of how the universe works, and we might even discover new physics as a result.

Unlike the archeologist who must unearth fossils and use carbon dating to discover our ancient history, astronomers have the advantage of observing different points of cosmic history in real time.

But it is only through our intellect and the collective efforts of science to improve our understanding that this is possible.

As we go about our daily lives, there is no way for our senses to perceive that one light signal is older than another, aside from our depth perception which is only useful to a few hundred meters. There is nothing fundamentally different about a light signal from a star and one from a light bulb.